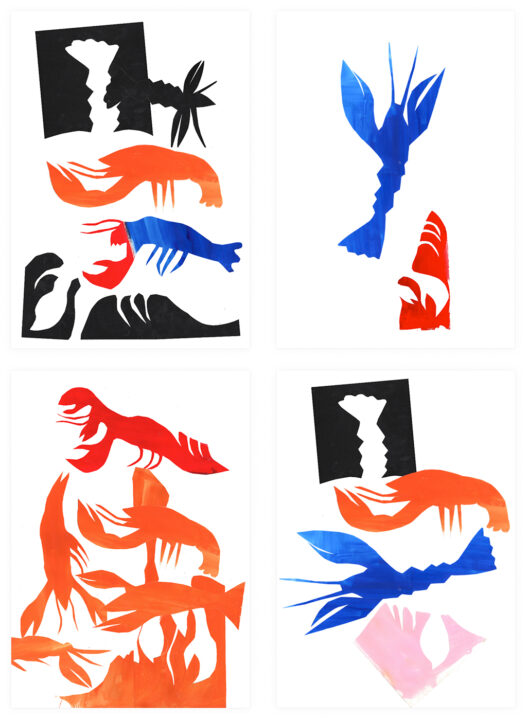

JUBG Edition by Reena Spaulings

4 unique motifs, Holiday, Flight, Ruckus, Apartment, 2025, fine art print on 190 g/m² satin paper, each 84,1 x 59,4 cm, signed, dated, numbered certificate, edition of 15 + 5 AP.

Edition set of all 4 motifs No. 1-5 / 15 + 5 AP for 700 € (exclusive VAT + shipping)

Each motif No. 6-15 / 15 + 5 AP for 200 € (exclusive VAT + shipping)

Ab jetzt wird durchgeblüht: Music for Anrainer of Airports / Ich habe keine Fragen, nur Antworten, 2025, 12” Vinyl LP + unique artwork, signed, dated, numbered, edition of 10 + 5 AP.

400 € (exclusive VAT + shipping)

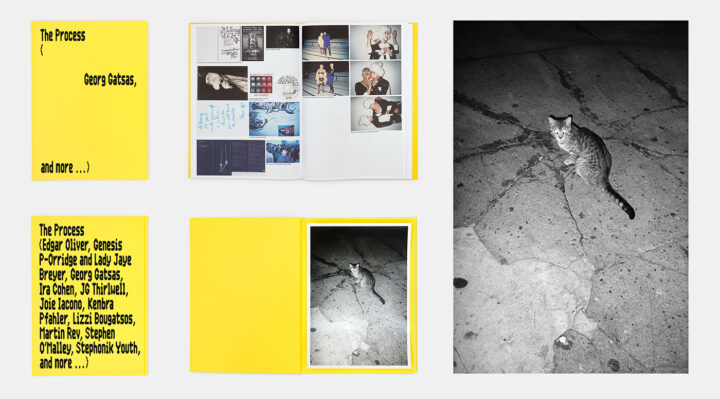

JUBG Edition by Georg Gatsas

Artist book The Process, 144 Pages, 561 four-color process printing plates, 31 x 22,5 cm, with an essay by Ethan Swan. Limited edition to 500 copies. Graphic Design by Dorothee Dähler, Kaj Lehmann. Published by light-years. + Special edition print: Cat, 2006 / 2025, silver gelatin print, 30 x 20 cm, signed, dated, numbered, edition of 15 + 5 AP.

Book + print 200 € (exclusive VAT + shipping)