JUBG with Nie Pastille and Philipp Schwalb at

Het Zuid Manifest: Carola Loves Carlos

Rotterdam, March 26 – 29, 2026

www.ribrib.nl

In collaboration with more than 40 local and international artists and 20 galleries and institutions, artworks are placed across everyday spaces in Charlois. From a barbershop and a vacant store to a theme park under construction, a dramaturgy is created that brings to the surface what was already present in both artwork and location, yet remained unspoken. Het Zuid Manifest is a program of Rib and is conceived and curated by Maziar Afrassiabi.

Participating galleries and institutions

Agence de voyages (Paris), CBK Rotterdam (Rotterdam), De Ateliers (Amsterdam), Esther Schipper (Berlin), Etablissement d’en Face (Brussels), Galeria Alegria (Barcelona), Gauli Zitter (Brussels), Guido W. Baudach (Berlin), JUBG (Cologne), KIN (Brussels), Kunsthalle Lingen (Lingen), Mieke van Schaik (Den Bosch), MORPHO (Antwerp), O Gallery (Tehran), Galerie Oskar Weiss (Zürich), Shahin Zarinbal (Berlin), Stokker Jaeger (Amsterdam), MMXX (Milan), Unseen X Keep an Eye Photography Stipendium HKU (Utrecht) and more to be announced.

Participating artists

Lucy Azatyan, Darly Benneker, Tina Braegger, Jakob Brugge, Iyanla Etnel, Olivier Foulon, Paul Goede, Thomas Helbig, Jack Jaeger, Erwin Kneihsl, Wjm Kok, Vesta Kroese, Gabriel Kuri, Daniel Laufer, Sam Marshall Lockyer, Bernd Lohaus, Sinaida Michalskaja, Neda Mirhosseini, Kenichi Ogawa, Nie Pastille, Joke Robaard, Philipp Röcker, Nora Schultz, Philipp Schwalb, Ken Sortais, Ken Stoove, Harald Thys & Jos de Gruyter, Noor van der Wal, Adrienne Verburg, David Weiss, Hussel Zhu, Cosima zu Knyphausen, Martha Olech and more to be announced.

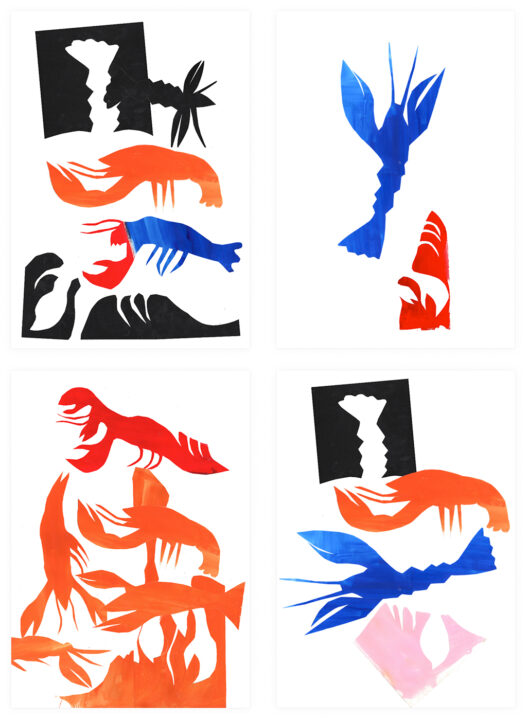

JUBG Edition by Reena Spaulings

4 unique motifs, Holiday, Flight, Ruckus, Apartment, 2025, fine art print on 190 g/m² satin paper, each 84,1 x 59,4 cm, signed, dated, numbered certificate, edition of 15 + 5 AP.

Edition set of all 4 motifs No. 1-5 / 15 + 5 AP for 700 € (exclusive VAT + shipping)

Each motif No. 6-15 / 15 + 5 AP for 200 € (exclusive VAT + shipping)

Ab jetzt wird durchgeblüht: Music for Anrainer of Airports / Ich habe keine Fragen, nur Antworten, 2025, 12” Vinyl LP + unique artwork, signed, dated, numbered, edition of 10 + 5 AP.

400 € (exclusive VAT + shipping)

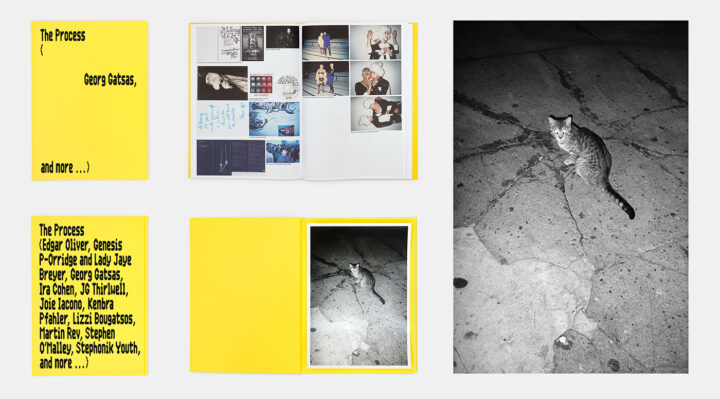

JUBG Edition by Georg Gatsas

Artist book The Process, 144 Pages, 561 four-color process printing plates, 31 x 22,5 cm, with an essay by Ethan Swan. Limited edition to 500 copies. Graphic Design by Dorothee Dähler, Kaj Lehmann. Published by light-years. + Special edition print: Cat, 2006 / 2025, silver gelatin print, 30 x 20 cm, signed, dated, numbered, edition of 15 + 5 AP.

Book + print 200 € (exclusive VAT + shipping)